News

News > Extract

Read an extract: A World with No Shore

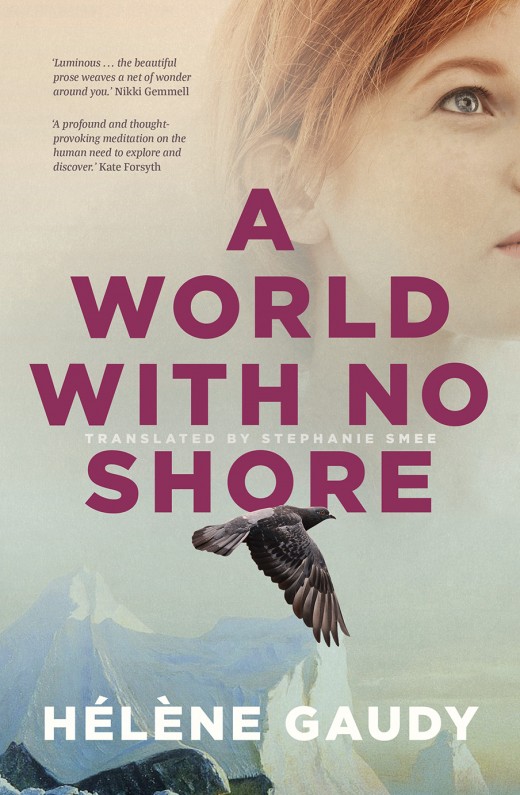

From the conquest of the skies to the exploration of the Poles, Hélène Gaudy's haunting and brilliant award-winning novel, set in the ethereal landscape of the Arctic, reflects on the human need to discover, describe, conquer and ultimately shrink the world. Read an extract.

CONTACT

Copenhagen, November 2014

They are standing in front of a dark shape: an immense fallen balloon, as still as an animal washed ashore. There is, in the taut fabric, a breath of wind to be felt, as if some enormous mouth were still inflating it. One of them makes as if to move, the other is motionless, already. They were in mid-air and now here they are, contemplating the inert mass of their dream.

The image bears all the uncanniness of those early days of photography, of the first portraits of strangers and spectres. It is riddled with a multitude of insect-like dark flecks. Its surface is velvet grey, glimmering with the vague reflections left behind by the light, smooth as cloth, deep as the sea, a scattering of abstract constellations, markings, sooty crackling, edges leaking like ink, traces of too powerful a light that obliterates the landscape, or vapour that dissipates every nuance of black.

If you look past these blemishes, if you try to lift them like a veil, what remains, next to the mass of the balloon, black on white, are two silhouettes, dangling in the void as if by an invisible hand. You can only tell where the ground stops, where the sky starts, by the position of their feet. Without those figures, you might just be looking at an icy cliff or a sugar lump held between two fingers.

There is nothing to indicate their sex, their age, only what we have all understood since childhood to represent a human shape: two arms, two legs, a blockish torso, a small head. And yet quickly we sense they are men – is it because of the weapons, black dashes at their belts? Or because at the turn of the twentieth century there were so few women photographed anywhere except in front of a painted backdrop or salon wall-hanging? If there are two of them in that image, there must be a third holding the camera, another man, invisible, to whom we owe the photograph.

It stands out, among others, at Copenhagen’s Louisiana Museum – an elegant, white structure, colonnades and terraces reminiscent of the state of Louisiana which, you might guess, has lent this place its name when in fact it was named after the three successive wives of its founder, all called Louise, and all of whom you can easily imagine strolling one after the other across the luscious lawns that tumble down to the Baltic.

Across the water is Sweden. On a fine day, you can just make out the coastline.

Sometimes, an image breaches the unspoken agreement entered into with all the others – that we see them as surfaces, as memories, that we accept that what we are looking at only exists now behind a frame of glass or paper. Every now and then, one of them makes us pause. Our eyes are used to taking in everything without seizing on anything; this eases their task, allows them to rest. Sometimes we stop. To look.

And then the vast rooms of the museum release the space hinted at by the photograph, the growl of the sea intrudes more and more, bringing with it fragments of a northern land that is as unknown as it is familiar, of some white void that might be carried like an island within us all. There might be a lake, a glacier, fir trees and reindeer, then fewer and fewer trees, nothing but the cold and the light.

Things have changed scale; the image now takes over the room. The beginnings of a story seem to be hidden within it, something spills out from it, something unfinished, the outline of narratives to be rewritten, working backwards, since the image has just become the new point of departure.

The eye is a photographic plate which is developed in the memory. There are other images to be found, somewhere there, between lens and imprint.

THE DISAPPEARED

REVEALING

Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, September 1930

The image is not yet complete, it is still just a fragment, caught among so many others, fragments of a film that has spent years under the snow, in one of the most remote landscapes on earth. It is so water-logged that the sensitive material adheres to the finger touching it. It has suffered significant deterioration. It is well past its expiry date. One thing is certain: there is very little hope of being able to decipher from it anything resembling a narrative.

A man is holding it in his nervous hands, his expert but nervous hands, trying to stop himself trembling. His name is John Hertzberg. He is an experienced photographer and technician. On this particular day, he is dealing with an entirely unprecedented set of circumstances: hidden within that film is a mystery that has unsettled all of Sweden for over thirty years. He has it in his hands, but the slightest careless gesture by those same hands could consign it to darkness. It is up to him, as he himself wrote, to firm up these traces, to restore life to the scenes remaining hidden within.

There is a gravity in this moment, taking place behind the thick walls of Stockholm’s Royal Institute of Technology. With the greatest of care, Hertzberg unrolls the films which are all pressed together.

In addition to these blank rolls, one of which is wrapped in a scrap of the changing bag from the darkroom, soon he is looking at a roll of film taken from the body of the camera and, in copper canisters, another seven rolls, four of which have been exposed.

Each strip includes forty-eight 13 x 18 centimetre format images.

There is often little faith in the enduring nature of photography – exposed to the atmosphere, materials deteriorate and any contrasts could well vanish, be lost, leaving nothing behind. It does not share the noble and enduring reputation of painting, whose very substance reveals the stages, the regrets, the artist’s signature behind the landscape, the vestiges of preparatory drawings, layer upon layer for whomever wishes to notice them.

A photograph, you might say, generates itself, it appears fully formed, and it is only when you develop it yourself – when the paper is plunged into stop baths, when it takes on varying degrees of contrast, of intensity, when you experiment with the numerous possible ways it can be handled – that you understand the significance of the actions which have brought it to life, understand its fleeting nature, attributable to choices made, to mishaps.

Hertzberg is well aware of the power he wields over the images. He has mastered a new procedure: using autochrome plates on which, with the help of microscopic granules of potato starch, it is possible to re-create every colour under the sun. He knows how to filter the light and bring out the tints on the plate through the subtle interplay of the powders, much as the pointillist painters do. He knows how to create the most faithful print possible from what was once living, indeed even how, after the event, with some delicate handling, to give it the precision it was lacking. But he is also readying himself to discover the surprises it may be keeping in store.

Hertzberg works painstakingly, he is on edge. This message that has been sent to him through the mists of time must not be impaired. He is after a product which will reveal rather than damage, strip the superfluous without erasing the essential. He opts for pyrocatechol, to oxidise the silver bromide, absorb the blue and purple spectrum, intensify the salts.

Soon he has dozens of photographs before his eyes. He is the first custodian of these remnants, and he will remain the only person to have had contact with them when there was still something dynamic about them, when it was as likely they be ruined as be revealed – a flame that the slightest gesture might have extinguished. Later, the negatives, poorly conserved, will deteriorate, taking with them the sharpest contrasts, those areas that had remained hazy, the miniscule details that his methods, no matter how meticulous, had been unable to bring to light. All that remains of those images is what Hertzberg himself was able to detect in them. Should something have escaped his attention, that something has been irretrievably lost.

Some of them are much too pale, others overexposed. Soon it is possible to make out the texture of the ice revealing ravines, wrinkles which break into the white, carving it into dense blocks. At times, it is a mountain but it may also be an animal reclining on its side. And then, they appear: three men looking back at him. Three men who, soon, will be looking back at us.

These precise techniques, these hours of solitude, these measured gestures, all of it is necessary to render visible the traces of the way these bodies moved through the snow, of their energy, of the epic nature of the journey. Three men are returning to life, in silence, in darkness, reduced, like tribal shrunken heads, transformed into symbols on the paper.

Thirty years earlier they disappeared while trying to reach the North Pole in a balloon. Their names were Nils Strindberg, Knut Frænkel and Salomon August Andrée.

Absence had made mythic creatures of these three men, phantom pirates, drowned mariners, whose ghosts had continued to sail the seas. Sweden had never recovered from it, nor had the rest of the world. For thirty-three years, hypotheses had proliferated much like the theories that flourish surrounding the disappearance of a plane from the radar.

So often we feel more curiosity about those who slip into obscurity than interest in those who return, especially when the place where they have disappeared is more like an absence turned landscape. It was precisely those men who had to disappear – some went so far as to say it had been intentional. There are always some, in every era, every century, those who feel compelled to cross frontiers and fall down on the other side, and as much as we praise their courage and acclaim their exploits, it is the reassuring confirmation that the limits are there for a reason, which we cling to above all else – the belief that those who breach them end up foundering in a place where they will never know rest as we will never cease to invent lives for them, or miraculous escapes.

Ocean currents were compared with air currents, the men were said to have been carried on the whims of the wind, towards Siberia and beyond, a floating buoy was discovered, a messenger pigeon intercepted, bones were unearthed, remains exhumed: a thousand times over they were killed and brought back to life, such was the reluctance to accept their death.

And now, here they are. Visible at last. Revealed.

Hertzberg re-creates the long process that saw the pack ice absorb their flesh and blood, strips back, like dead skin, the pallid, sapping days, the snow, the light that burns as does the ice – everything which masked their image as their bodies, slowly, disappeared.

The darkest shapes are the first to emerge in the developing baths – their own silhouettes, then those of the tent, an upturned boat, rocky outcrops and, every now and again, a third, more blurry, silhouette, darker still: the photographer who has hurriedly returned to position himself in the frame having set the self-timer.

They are caught in various poses, next to the grounded balloon then alone on the pack ice or prodding a bear’s corpse with a rifle. Impossible to distinguish any one of them from their posture, from their way of holding themselves, from their faces devoured by the light. These shots seem to suggest they are interchangeable, that their individual existences are of no importance, straining as they are towards the goal they have set themselves.

In that same year of 1930, a certain Gunnar Hedrén will carry out the autopsy on what remains of their bodies, dispatched in crates to Tromsø in Norway’s far north. For two days, in the basement of the town’s only hospital, he will examine, with a small group of doctors, the bones barely covered by stiffened folds of clothes which always survive their owners, empty sacks aping their shape, barely distinguishable from a pile of rocks or sand. They will try to determine their cause of death, to decipher what remains.

Hertzberg, too, is occupied with a similar task. He is exposing the images just as the bodies are being opened up, exposing their insides. But the images will never again be closed up. Every day, every year, they will take on a different hue in the eyes of the men and women who come to look at them.

This is an extract from A World with No Shore by Hélène Gaudy, translated by Stephanie Smee. To read more, order A World with No Shore – out now.

Share this post

About the authors

Born in Paris in 1979, Hélène Gaudy studied at the school of decorative arts in Strasbourg. She is a member of the Inculte collective and lives in Paris. She is the author of six novels and has also written some dozen books for children.

More about Hélène Gaudy

Stephanie Smee left a career in law to work as a literary translator. Recent translations include Hannelore Cayre’s The Inheritors and The Godmother (winner of the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger award), Françoise Frenkel’s rediscovered World War II memoir No Place to Lay One’s Head, which was awarded the JQ–Wingate Prize, and Joseph Ponthus’ prize-winning work On the Line.

More about Stephanie Smee