News

News > Extract

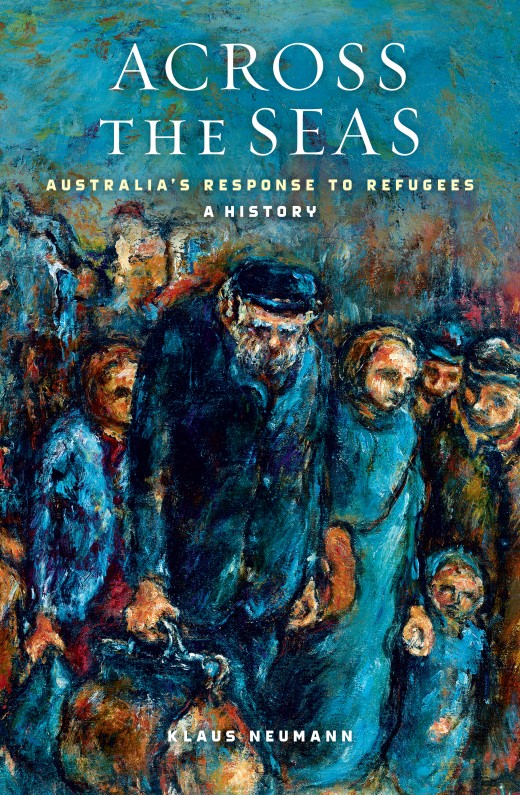

Special extract: Across the Seas

In this eloquent and informative book, historian Klaus Neumann examines both government policy and public attitudes towards refugees and asylum seekers since Federation. Read Arnold Zable's introduction to this important book online now.

Taking into account recent United Nations estimates of the numbers of internally and externally displaced people and asylum seekers worldwide, there are currently 50 million refugees. This is how it stands in April 2015, as the book goes to press.

The figures fluctuate. The estimates require constant adjustment. But judging by the expansion of conflicts in many parts of the world, the numbers may well rise. In the not-too-distant future we may also see populations from low-lying islands, coastlines and river deltas displaced by the impact of climate change. The challenge of how to respond to this chronic crisis is urgent and immediate, and will remain so well into the future.

In Australia the public debates over refugee policy are intense and vigorously contested. Many claims and assertions are made about past responses to refugees as being better or worse than contemporary responses, or as being better or worse when compared to those of other countries.

Given the amount of attention focused on the issue, it is surprising to learn that there has been only one comprehensive account of Australia’s immigration history, and that Across the Seas is the first full-length monograph about Australia’s response to asylum seekers and refugees since Federation: this, as Neumann says, in a country with a history that is marked by two key themes, Indigenous dispossession and immigration.

It takes time to explore what happened in the past. It demands the hard slog of research – wading through archives, parliamentary records, newspaper files, departmental statements, the proceedings of policy debates within parties, the records of lobby groups and successive governments – in order to see what was actually said and done, and who said it and did it. Neumann places himself in the eye of the storm in order to sift through the evidence, and synthesises it into an accessible narrative. It is a mammoth undertaking. The result is a far-reaching chronological account written with clarity and insight.

The chronicle begins with Federation in 1901 and ends with the federal election campaign of 1977. By this time, says Neumann, the public responses to refugees that we are now so accustomed to had been fully formed. His account thereby sheds much light on the present. It allows the reader to discern both the parallels with the past and the uniqueness of contemporary policies.

Neumann employs both the wide-angle lens and the close-up. We should never lose sight of the individual refugee, and the tales of the countless men, women and children who have chosen to make perilous journeys, risking all on a gamble for freedom. This is encapsulated in a seminal incident that took place beyond the timeframe of Neumann’s book, but which can be better understood because of it.

In other words, we saw no individual faces. We heard no specific voices. We did not know, for instance, that the Hazaras, the major group among the rescued, had fled the horrors of the Taliban. Instead, we received images of a horde of people crammed on the deck of a steel freighter. A horde inspires fear and misunderstanding.

Neumann does not lose sight of the individual. His account is studded with anecdotes, stories and significant case histories. It is humanist in orientation and empathetic to the plight of refugees, but most concerned with documentation. To read it is to be informed and better armed to take on the challenge.

Thus, we see, for instance, that while some advocates may believe that today’s hostile community and government attitudes towards refugees is unprecedented, there were in fact, Neumann points out, ‘proportionately at least as many virulent xenophobes’ among those who responded to refugee challenges in the past.

This applies equally to the late 1930s and 1947, as evidenced in the negative responses to the potential arrival of pre-and post-Holocaust Jewish refugees, and to 1977, as can be seen in some of the responses to the challenges posed by the Indochinese refugees who made up the first wave of ‘boat people’. In contrast, both in the past as in the present, there were many advocates who campaigned tirelessly for refugees. Neumann’s account brings to light the efforts of many unsung champions of refugee rights whose foresight and compassion have fallen below the radar.

The book is studded with unexpected facts, gems of information and statements that betray the prejudices of particular times. We learn, for instance, that Thomas Hugh Garrett, the assistant secretary of the Department of the Interior, after visiting Europe on the eve of war to investigate the selection of suitable ‘alien immigrants’ for resettlement, asserted, in a letter to his departmental secretary, that Polish Jews ‘are the poorest specimens outside blackfellows that I have seen’. Yes, dear reader, this is what he wrote.

We learn that the first ‘boat people’ were, arguably, the eight West Papuans who landed on Moa Island in the Torres Strait on 16 February 1969, after a harrowing month-long journey by raft, in flight from the Indonesian occupation of West Irian. We learn that until the 1970s, with the arrival of Indochinese refugees, government policy was predominantly based on pragmatic rather than humanitarian concerns. Neumann contends that it was not until 1977 that a government defended its approach to refugee policy by drawing on the language of humanitarianism and by invoking Australia’s international legal obligations.

We learn of the succession of refugee crises that continue to erupt unexpectedly. Each challenge is directly connected to international events: the fall of Saigon in 1975, the 1973 CIA-backed coup against the Allende government of Chile, the relentless civil war in Lebanon and the brutal division of Cyprus in 1974, to mention just a few. Each crisis demanded a response. Each generated debate and challenged the conscience of the public.

We see also how the measure of the suitability of specific ethnic groups has changed over time. Neumann sheds light on what La Trobe academic Gwenda Tavan has called, in her book of that name, ‘the long, slow death of White Australia’. We see the pragmatic reasons for the shift, the interplay between an urgent need for new sources of immigrants to make up for severe post-war labour shortages, public opinion, international pressures and the rise of the newly independent nations of Asia and the Pacific.

While Australia may have officially abandoned the White Australia policy by the 1970s, the debates over the suitability of particular groups for resettlement have never ceased. In 1947 the first source for immigrants remained the British Isles. ‘Non-White’ immigrants included not only Chinese and Japanese, but also Jews and southern Europeans. As these groups became accepted as part of White Australia, other groups were placed beyond the boundaries of acceptability.

It is a great irony that in recent years, as Neumann points out, Lebanese and Vietnamese Australians could demonstrate their belonging to White Australia ‘not least by joining the chorus that demanded the exclusion of Hazara, Iranian and Tamil “boat people”’.

To turn the spotlight back on the present: in 2015, at the time of writing, asylum seekers who have in recent years sought protection in Australia are incarcerated both in onshore and offshore detention centres. Many others remain in limbo out in the community on various types of temporary visas. The centres on Nauru and Manus Island are hellholes, the inmates’ agony compounded by isolation. Out of sight, out of mind is the name of the game. Journalists are not permitted. Information is hard to come by. Disturbing claims of sexual abuse, beatings, self-harm and attempted suicides are denied, but proven true on the rare occasions when independent investigators are allowed access.

As Neumann reiterates in his conclusion, ‘there is nothing self-evident or natural about Australia’s current response to asylum seekers and refugees’. He hopes instead to have encouraged the reader ‘to imagine alternative futures’, which ‘take into account Australia’s capacity to assist people in need of a new home, its responsibility as a regional power, its legal obligations as a member of the international community, and, most importantly, the precarious circumstances of the men, women and children who are seeking Australia’s protection’.

As one of the first readers of Across the Seas, I will take up the challenge. The word ‘imagination’ stems from the word ‘image’. An act of imagination is an act of seeing, and I have seen alternative futures at work.

Take, for instance, Melbourne, the great cosmopolitan city in which this book is being published. In this sprawling metropolis the impact of past policy is made visible. We witness the creativity and energy of the diverse and varied communities that have made their way to our shores and been allowed to settle, whatever the reason. We see the impact of the many cultures whose migration stories Neumann has documented. We see, for instance, how within just a few years the local Hazara community has helped transform the city of Dandenong into a thriving metropolis.

I end with one last example of the future in action, encapsulated in the tale of a notebook. The notebook is blue, the spine reinforced with tape. The covers are fraying at the edges. The pages list every person assisted by the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre since June 2001, the month it opened. The notebook is full. It contains 7579 names. Pick any name at random and Kon Karapanagiotidis, the CEO and founder of the centre, knows the story. A second notebook is filling. Fourteen years after the centre opened, the number of those it has helped is now over 10,000.

The centre, which began as a shopfront, is now a massive undertaking. To see the daily presence of hundreds of asylum seekers, volunteers and supporters, and to observe the empowering programs and expanding facilities, is to see an alternative future at work. The centre is a haven, a bridge between past and present, and a model of what is possible when Australian citizens reach out to the latest arrivals.

Across the Seas shows us what has happened in the past, so that as we move forward we are armed with the facts and aware of the continuities and the departures, and of some of the many options we can draw upon. It helps us imagine a more compassionate future.

Arnold Zable

Writer, novelist and human rights activist

April 2015

Share this post

About the author

Klaus Neumann is working for the Hamburg Foundation for the Advancement of Research and Culture. His 2006 book In the Interest of National Security won the John and Patricia Ward History Prize, while his Refuge Australia: Australia’s Humanitarian Record (2004) won the Australian Human Rights Commission’s Human Rights Award for Non-Fiction. He is currently writing a book about local German public and policy responses to asylum seekers and refugees.

More about Klaus Neumann